Earlier this year, I wrote a short story chronicling my efforts to learn more about my maternal grandfather’s emigration from Kameyama, a small village near Hiroshima, to Canada. Starting with an old photograph and vague family stories about Canada, I delved into various archives and genealogy resources. It was a fascinating journey, as I not only uncovered information about my grandfather, but also learned about the experiences of Japanese emigrants in Canada.

The story was recently published on Discover Nikkei, a community website about Nikkei identity, culture, and history. Below is copy of the story (with added subheads for clarity).

Tracing my grandfather’s journey from Hiroshima to Canada

Obaachan—my mom’s mom—passed away in 2000 in Los Angeles. Since then, her photo albums have been stored at my parents’ house. As the family historian, I often look through them during visits and, over the years, I would ask my mom questions about who was pictured and how they were related.

“Who’s the guy in this photo, mom?” I asked one day, as I pulled out a small sepia-colored photo from an album. Small enough to fit in the palm of my hand, the photo showed a dapper man wearing a fedora and a suit posing in front of a large car.

My mom, who sat at the kitchen table next to me, put her glasses on and gave the photo a quick look.

“Oh, that’s my father,” she said. “He died when I was a baby so I didn’t know him.”

Curious to learn more, I prodded my mom for information. Finally, she shared the few details she knew about her father.

My grandfather’s emigration from Kameyama Village

Photo of Masao Nakaki (Personal photograph)

His name was Masao Nakaki and he was from Kameyama, a village near Obaachan’s hometown of Kabe in Hiroshima prefecture. He came from a farming family and had one sibling that she was aware of—an older brother. His birth date was unknown but he was older than Obaachan.

He was supposed to marry Obaachan’s older sister, but she refused the arranged marriage. As the more obedient second daughter, Obaachan married him, but soon after the wedding, he left for Canada to work. While he was away, Obaachan went back to her own family home, which was unusual at the time, as wives usually remained with the husband’s family after marriage.

My mom had no idea why Masao went to Canada or how long he was there, but she recalled that he returned to Japan before World War II began. He had saved enough money to provide a comfortable life for Obaachan and their first child, my aunt Keiko, who was born in 1943. They lived on the outskirts of Hiroshima until the atomic bomb was dropped by the US, after which they fled to the mountains. My mom, Masako, who was named after Masao, was born in 1946. He died six months later, leaving Obaachan a widow with two young daughters.

More questions than answers

After hearing the story, I had even more questions. Why did he marry and leave for a foreign country right away? What kind of work did he do in Canada? Was he always planning to return to Japan or did he want to emigrate to Canada?

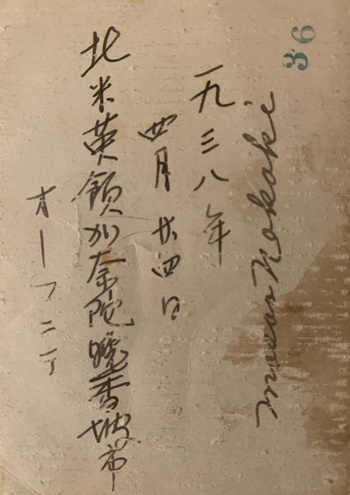

On the back of Masao Nakaki’s photo (Personal photograph)

My mom did not have any answers. I flipped the photograph and on the back was written “Masao Nakaki” in English cursive script—a clue that it may have been taken outside of Japan. The date was April 24, 1938. One line of text was written in kanji characters. The first few characters translated to “North America English Territory” but my mom was unable to translate the remaining ones. A final line of text written in katakana, a Japanese phonetic alphabet used for foreign words, spelled out “oufunte”, which seemed to be a meaningless word.

Intrigued, I set out to find more information. Because Masao had traveled to Canada, I searched the immigration records on the Library and Archives Canada website. There, I found two records for Masao Nakaki: one with an arrival date of June 13, 1929 and the other with an arrival date of May 20, 1935. Each record was linked to a passenger list with information such as name, age, country, place of birth, nationality, race, occupation, destination, and nearest relative.

I was surprised to find two records because my mom only knew of one trip to Canada. I closely checked the passenger lists and confirmed that the same Masao Nakaki had entered Canada twice, once at age 23 and once at age 29.

According to one passenger list, 23-year-old Masao boarded the S.S. Africa Maru in Kobe, Japan on May 29, 1929 and disembarked in Victoria, British Columbia on June 13, 1929. He was from Kameyama, a village in Hiroshima prefecture, and this was his first visit to Canada. His father, Ryukichi Nakaki, was listed as his nearest relative. He had been a farm laborer in Japan and his intent was to do similar work in Canada for Otokichi Okazaki of Port Hammond, British Columbia, who was noted as his employer.

With this information, I was able to confirm the family story that he was from a farming family and went to Canada to work and that there was a large age gap between Masao and Obaachan, as Masao was born in 1906 and Obaachan was born in 1918.

Then, I found a 1931 Canadian census document for Maple Ridge, British Columbia that listed Masao as a berry farm laborer living with Otokichi Okazaki and his family. I noticed that there were many Japanese families listed on the same page. The census document raised a couple of questions: why were there many Japanese in Maple Ridge and why was Masao living with his employer?

Japanese in Canada

It turns out that in the early 1900s, Maple Ridge was a district in British Columbia that was home to a thriving Japanese farming community. The district included small rural communities such as Port Hammond, Haney, Whonnock, and Ruskin. Located about 25 miles (40 km) east of Vancouver, the district was bounded by the Fraser River to the south and the Golden Ears Mountain to the north.

While many Japanese went to Canada seeking income, adventure, or both, with the intent of eventually returning to Japan, others dreamed of owning and farming their own land. Beginning around 1904, Japanese immigrants began to farm in the Maple Ridge area, first leasing and then eventually buying land.1 They acquired land that was inexpensive but required a lot of clearing—poor, unused, or stump-covered land—before strawberry plants and raspberry canes could be planted. These farmers worked hard and found success, which attracted more Japanese to the area.

Japanese women and children picking strawberries in Whonnock in 1941. Maple Ridge Museum & Archives, P06675.

However, increased immigration led to the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment. This resulted in the Hayashi-Lemieux Agreement or Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1908, which restricted the number of Japanese passports issued to male laborers and domestic servants to 400 per year. Because wives and children were exempt from this agreement, picture brides—women who married by proxy in Japan and then traveled overseas to meet their husbands for the first time—immigrated in large numbers between 1910 and 1928. Families formed and grew, increasing the Japanese population. In 1901, 4,738 Japanese were living in Canada; by 1921, there were 15,868, of which about 95 percent lived in British Columbia.2 In response, the agreement was revised in 1928 to further limit the number of immigrants to 150 per year, this time including wives and children.

Despite these restrictions, the Japanese community in Maple Ridge flourished. As the number of families grew, Japanese language schools, community halls, and Buddhist temples were constructed. By 1928, Japanese farmers produced 92% of the strawberry crop and 75% of the raspberry crop in the region. By 1930, a year after Masao first arrived in Canada, there were 200 Japanese landowners in Maple Ridge and, by 1940, there were 250.3

My grandfather’s status as a “yobiyose”

Masao may have entered the country as a yobiyose immigrant sponsored by Otokichi Okazaki, who owned a berry farm in Maple Ridge. Yobiyose, which means “to call over” in Japanese, were usually family members or fellow villagers who were sponsored by Japanese landowners in Canada for agricultural work.4 In exchange for 3 to 5 years of labor, the yobiyose were paid a wage, provided room and board, and received a monthly stipend. While some yobiyose returned to Japan after their contract ended, others opted to remain in Canada.

The second passenger list indicated that Masao had departed Canada on October 15, 1934 via Vancouver, which meant he had been in Canada for five years. Five months later, on March 25, 1935, he was issued a Japanese passport in Hiroshima prefecture. On April 29, 1935, he boarded the S.S. Empress of Russia and arrived in Victoria, British Columbia on May 20, 1935. He was a laborer traveling to join a friend, Yasutaro Morikawa of Port Hammond, British Columbia. His wife, Chiyoko Nakaki of Kameyama, was listed as his nearest relative.

During his brief stay in Japan, he married Chiyoko, my Obaachan, who would have been 16 or 17 years old at the time. This aligned with the family story, but it did not answer the question of why he would marry and then turn around and leave for Canada.

Yasutaro Morikawa was likely Masao’s employer as well as friend. As a prominent landowner whose hometown was Kameyama village, he may have had a personal connection with Masao as well as the means to sponsor him in Canada. Yasutaro Morikawa had arrived in Canada in 1904, eventually bought land in the Maple Ridge area, and became a successful farmer, growing apples, strawberries, and garden vegetables.5

Morikawa family and friends posed outside their home on 216th where the Maple Ridge Funeral Chapel is located today. The photo was taken circa 1932. They only enjoyed a decade in the home before they were interned. Maple Ridge Museum & Archives, P06607. NOTE: The museum confirmed that the family head in this photo was Yasutaro Morikawa, who came from the same village as Masao Nakaki and who was also listed as Masao Nakaki’s Canadian contact on the 1935 passenger list. Masao most likely worked for this family on their farm.

At this point, the document trail had run out and any additional details of Masao’s life in Canada remained a mystery. Because the Canadian government did not keep track of people who departed Canada (unless they returned, at which time their prior departure dates were recorded), I was not able to confirm when he returned to Japan.

I looked again at the family photograph of Masao dated April 24, 1938 and wondered about the unknown kanji characters. I showed it to a Chinese friend, who said that the characters phonetically spelled out “Canada Vancouver”. In Chinese and possibly older Japanese, characters are chosen to approximate the sounds of foreign words rather than their meaning. In modern Japanese, kanji characters are not used to spell out foreign words, which was why my mom was unable to make sense of them.

Based on this new information, the line of katakana—“oufunte”—that was written on the back may have referred to a place in Vancouver. I looked on a map and guessed that “oufunte” could be Japanese shorthand for the Orpheum Theater, a landmark movie palace in 1930s Vancouver.

Departing for Japan

On the day the photograph was taken, Masao may have been in Vancouver waiting to board a ship back to Japan. Dressed in a suit and hat, he may have been spending his last few hours in Canada in front of the Orpheum Theater or strolling Powell Street, which was the heart of the Japanese community in Vancouver.

If he did leave in 1938, he timed it well. Japan’s aggression toward China, which began with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and culminated in the start of full-scale war in 1937, heightened anti-Japanese sentiment in Canada. By the time Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941, fears of a Japanese invasion had intensified, especially along the British Columbia coast.

In 1942, the Canadian government detained and incarcerated more than 90% of the Japanese-Canadian population (about 21,000 people) and placed all Japanese property—homes, farms, businesses, and personal property—under “protective custody” until after the war. The following year, the Canadian government liquidated the property instead, using the meager proceeds to help pay for the costs of incarceration.

After the war ended, Japanese farming communities like Maple Ridge did not recover. Dispersed across Canada and barred from returning to within 100 miles of the British Columbia coast until 1949, many rebuilt their lives in other parts of the country. Of the 300 Japanese-Canadian families from Maple Ridge that were detained and incarcerated, only 7 returned. Indeed, Masao’s employers—Otokichi Okazaki and Yasutaro Morikawa—did not return to Maple Ridge. An obituary for Otokichi was published in 1987 in the Toronto Star newspaper. An obituary for one of Yasutaro’s sons noted that, after the family was incarcerated, they relocated to Toronto.

Masao never traveled back to Canada. The family story is that Masao returned to Japan in weak health. Would he have stayed in Canada if he had been healthy? Did he intend to build a new life in Canada? Obaachan probably knew but she never talked about him, at least to me. There may have been letters or diaries detailing Masao’s thoughts, but I have not seen them.

Masao must have been quite a character, a bit of a wanderlust who set out in search of his fortune and spent eight years of his life overseas. He must have seemed worldly in Obaachan’s eyes. While I am grateful to have uncovered some details of Masao’s journeys to Canada, I am still left with questions for which answers may never come to light. Perhaps a future trip to Hiroshima may turn up a few unexpected surprises.

Notes

- Michiko Midge Ayukawa, “Creating and Recreating Community: Hiroshima and Canada 1891-1941” (PhD diss., The University of Victoria, 1996), 150–54.

- W. Peter Ward, The Japanese in Canada (Canadian Historical Association, 1982), 4, 7.

- John Mark Read,“The Pre-War Japanese Canadians of Maple Ridge: Landownership and the Ken Tie.” (MA diss., The University of British Columbia, 1975), 53–54.

- Ayukawa, “Creating and Recreating Community,” 158–59.

- Ayukawa, “Creating and Recreating Community,” 182–83.

Leave a Reply